Another year has passed, during which I, unfortunately, have been too busy making the money I need to survive to engage in what I really love to do. Don’t get me wrong—I enjoy my current writing and editing work, and I am very thankful to have the opportunity to do it. But it takes up all my energy. Perhaps the new year will bring me to a place where I can once again do the writing that truly moves my spirit and feeds my soul.

To get the ball rolling again, I present a reworked version of an essay that I composed back in 2010, while Jamie and I were living in Patagonia. Although the essay had not generated much interested at the time, recent events here in Uruguay have thrown a spotlight on the country I am so proud to call my home. Our hobbit of a president has, of course, gained international acclaim, as has Uruguay’s pioneering marijuana legislation, the taking in of six Guantanamo detainees, and the president’s role in mediating the opening of US diplomatic relations with Cuba. I feel that this profile contrasting the philosophies of the Catalan-Uruguayan artist Joaquín Torres García and the Russian–United Statesian author Ayn Rand offers some interesting insights into the national character of this little country that has become a world leader in social progress and human rights under the leadership of President Mujica. The changes I have made to the original were to correct a few errors of fact that I had made, to clarify and smooth out the essay a bit, and to add some context pertaining to recent events. I can only hope that my thoughts and observations as a foreigner hit somewhere close to the mark.

Joaquín Torres García vs. Ayn Rand: A Unique Profile of the Uruguayan National Character

After visiting the Museo Joaquín Torres García in the heart of Montevideo’s historic Ciudad Vieja, I became intrigued by the contrasts between a culture that gave birth to Torres García’s elegant philosophy of art versus the culture that I came from in the United States that, in its deeply held esteem for individual rights and privileges, finds many supporters of the ungainly philosophy of Ayn Rand. In Uruguay, Joaquín Torres García’s art and ideas have become emblematic of the national character. From the philosophy of constructive universalism, which he developed through decades of artistic exploration first in Europe and then in Uruguay, emerged his iconic images espousing an expansive American aesthetic. In the United States, the writings of Ayn Rand have engendered a divisive political movement. From her literature arose the philosophy of objectivism, which she developed to promote the ideals of individual rights and laissez-faire capitalism. Both thought systems include a conception of art as a language of ideas with a social purpose. Yet they could not be farther apart in their characterizations of the nature of humanity and society. One sees society as the invigorating cultural connection of individuals across space and time, while the other sees society only as a hindrance to the pursuit of happiness. One draws strength from the unity of all, the other finds strength to be solitary. One is connective, the other, detached.

Nine Months in Uruguay

When I spent nine months living in Uruguay, beginning in June 2009, my understanding of castellano was sufficient for me to intuit the culture to a fair degree. This matters greatly in Uruguay because this small nation, tucked away between the behemoths Argentina and Brazil, has developed, in its 186 years of existence as an independent nation, a unique cultural understanding that abounds in subtleties that are easily missed by the undiscerning observer.

What I discovered during my time here was that, underneath the general sense of contentment and positive outlooks with which friends and families would gather around the parilla to grill beef, watch fútbol, or for the youths, hit the dance clubs until well beyond the dawning of the new day, lie the hard-learned lessons of more than a decade of military dictatorship, the most recent incidence in a complicated history of political violence and regional warfare. The benefits of these lessons learned were coming to fruition during my time here, in the form of the election of an ex-Tupamaro guerrilla fighter who had been imprisoned in isolation at the bottom of a deep well for many years during the dictatorship. Everyone I spoke to—mostly hard-working people, artists, artisans, and students who I encountered in the beach town of La Paloma, and later, in Montevideo—seemed anxious to find out what my understanding of this extraordinary achievement might be, and I was happy to show my appreciation of the pride in their voices and the tears welling in their eyes as they spoke of José “Pepe” Mujica, with his insistence on continuing to live at his humble flower farm, his practice of donating most of his salary toward progressive causes, his outrageously folksy 1987 Volkswagen Beetle, and his election-night declaration that his gaining of the presidency was not victory, but continuity.

What I discovered during my time here was that, underneath the general sense of contentment and positive outlooks with which friends and families would gather around the parilla to grill beef, watch fútbol, or for the youths, hit the dance clubs until well beyond the dawning of the new day, lie the hard-learned lessons of more than a decade of military dictatorship, the most recent incidence in a complicated history of political violence and regional warfare. The benefits of these lessons learned were coming to fruition during my time here, in the form of the election of an ex-Tupamaro guerrilla fighter who had been imprisoned in isolation at the bottom of a deep well for many years during the dictatorship. Everyone I spoke to—mostly hard-working people, artists, artisans, and students who I encountered in the beach town of La Paloma, and later, in Montevideo—seemed anxious to find out what my understanding of this extraordinary achievement might be, and I was happy to show my appreciation of the pride in their voices and the tears welling in their eyes as they spoke of José “Pepe” Mujica, with his insistence on continuing to live at his humble flower farm, his practice of donating most of his salary toward progressive causes, his outrageously folksy 1987 Volkswagen Beetle, and his election-night declaration that his gaining of the presidency was not victory, but continuity.

I understood very well that the victory did not belong to the Frente Amplio, the left-wing political coalition that became the target of the US-backed covert anti-Communist manipulations that allowed the dictatorship to take hold after the 1971 elections, but rather, the real triumph was that of nonviolent political engagement. The Tupamaro movement had initiated a romantic, Robin Hood–style scheme for redistribution of wealth that escalated out of control. But they eventually developed a political wing and joined the Frente Amplio, beginning upon a peaceful path of creating change through legitimate participation in the political process. I understood the desperation with which the opposition party, during the 2009 elections, had tried to paint Mujica as a wild-eyed leftist who still had violent intentions at heart. And I understood the importance of Mujica’s acceptance speech recalling a patriarchy that went back to the very founding of the Uruguayan nation.

I understood this in reference to the love and admiration that the Uruguayan people hold for their founding father, José Gervasio Artigas. He was not only “the Liberator” of Uruguay, in military terms, but he is also revered as being a true renaissance man—a skilled outdoorsman, naturalist, and progressive social philosopher who played guitar and sang, knew the indigenous Charrúa people well, spoke eloquently, and proposed a visionary multicultural, multiethnic, federalist “American Plan” that was the western hemisphere’s first attempt at land reform, under the slogan, “Los más infelices serán los más privilegiados,” “The most unhappy will be the most privileged.” His personage expresses the marriage of democratic self-rule, imbibed with the fiercely independent spirit of the austere and self-sufficient gaucho, with socialist ideas about connecting all members of society together in order to create a synergistic whole that benefits all. Artigas’s philosophy persevered through the attempts of Argentina and Brazil to fold the Eastern Republic of Uruguay into their own New World empires. Then, in 1913, after nearly a century of constant rebellion raised by rural caudillos against the democratic rule of the urban intellectuals in Montevideo finally came to an end, ideology known as Batllismo set in motion programs for an “interventionist and redistributor” government with an ample body of social policies. This was the continuity to which Mujica had referred when reassuring the nation that his election was not such a radical turn of events for Uruguay.

I understood this in reference to the love and admiration that the Uruguayan people hold for their founding father, José Gervasio Artigas. He was not only “the Liberator” of Uruguay, in military terms, but he is also revered as being a true renaissance man—a skilled outdoorsman, naturalist, and progressive social philosopher who played guitar and sang, knew the indigenous Charrúa people well, spoke eloquently, and proposed a visionary multicultural, multiethnic, federalist “American Plan” that was the western hemisphere’s first attempt at land reform, under the slogan, “Los más infelices serán los más privilegiados,” “The most unhappy will be the most privileged.” His personage expresses the marriage of democratic self-rule, imbibed with the fiercely independent spirit of the austere and self-sufficient gaucho, with socialist ideas about connecting all members of society together in order to create a synergistic whole that benefits all. Artigas’s philosophy persevered through the attempts of Argentina and Brazil to fold the Eastern Republic of Uruguay into their own New World empires. Then, in 1913, after nearly a century of constant rebellion raised by rural caudillos against the democratic rule of the urban intellectuals in Montevideo finally came to an end, ideology known as Batllismo set in motion programs for an “interventionist and redistributor” government with an ample body of social policies. This was the continuity to which Mujica had referred when reassuring the nation that his election was not such a radical turn of events for Uruguay.

During my time living in the shadow of a lighthouse on a rocky cape extruding into the mighty Atlantic Ocean, I had written about Uruguayan culture in terms of its elegance of thought, which I saw as a colossal cultural achievement and the source of the nation’s heroic healing power. Indeed, visitors to Uruguay will hardly sense any lingering social problems associated with the not-so-long-ago dictatorship (1973-1985), while the same cannot be said of its more raucous neighbor, Argentina. Also in contrast to Argentina, Uruguay feels unrushed and easy-going, perhaps even simplistic. It is this basis of simplicity, I surmised, an appreciation of pure, unadulterated flavors, of life’s simple pleasures, of naked beauty and quiet moments, upon which layers of complexity can then be added in a way that they can be comprehended and internalized, building a cultural cognizance that is not so easily bewildered by smoke and mirrors or complicated issues or life’s inevitable contradictions.

For me, those reflections tended to revolve around this idea that Uruguay, because of its unique place in the world, its willingness to learn from its conflicted past, its cognition of complexity, and its amazing ability to enjoy the fruits of its natural and cultural abundance by means of what appears to be a very simple way of life, has managed to create the model social democracy. I found my reflections, to my own amazement, invoking imagery and leading to poetry, and from this process emerged unexpected ideas, such as the proposition that the secret to life is not just water, but the flow of water. I often reflected upon the significance of the fact that Uruguay’s highest denomination monetary note, the 1000-peso bill, portrays the cherished poet, Juana de Ibarbourou, on one side, and a lovely rendition of her collection of books on the other.

America

It was after I had moved from Uruguay to Argentinian Patagonia, while conducting research for my writing about my experiences in the two art museums I had visited in Montevideo in February 2010, when I began to recognize the link between Uruguayan artistic sensibilities and their politics. Could it be that their cultural duality of thought, which allows them to understand that individual self-determination can be enhanced by government policies aimed toward creating a society where more people are able to join in the ranks of those who find their lives fulfilling, comes from the same place in the human being that can recognize simple visual symbols and their conceptual context as representations of complicated ideas? Does the Latin American experience, which has produced a cultural narrative wherein what is real and what is fantastic share a broad and blurry boundary, and where the past lives tenaciously in the present, vivaciously, concretely, inescapably—does this shared experience facilitate the kind of connection of the parts with the whole that is largely absent in a nation that stands alone in the world, apart from its neighbors, distanced from its past, as sure of its inherent goodness as it is unaware of its connections with the world around it?

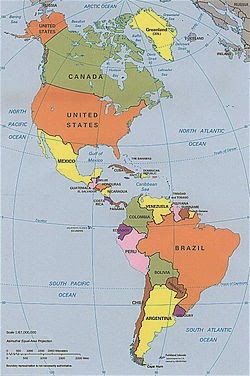

The United States stands alone in the Americas. Despite the fact that the people of thirty-five sovereign states and twenty-two territories associated with European nations can call themselves “American,” it is only those of the United States who claim the title exclusively for themselves. And for fifty years, only the United States refused to interact with Cuba—a stance that has negatively affected its relations with its neighbors for the past half century. But as Massimo Di Ricco points out in this Al Jazeera opinion piece, Pepe Mujica’s involvement in mediating the reopening of US diplomatic relations with Cuba is reflective of “a heterogeneous regional political bloc able to come to terms with ideological differences and to find common ground for regional coexistence in the name of progress,” with the best example of this being the peace talks between FARC and the Columbian government, with the participation of Chile, Venezuela, and Cuba. President Obama’s bold move is, indeed, of hemispherical proportions.

Joaquín Torres García Discovers America

When he returned from Europe to Uruguay in 1934, Joaquín Torres García adapted his aesthetic philosophy to a broader understanding that America is itself a connective force, embodying the transcendent power to link individuals with the entire universe.

When, as a young man, he moved with his family from Uruguay to Catalonia, Torres García was intent upon pursuing an education in classical art. During his many years in the region, he found work painting frescoes, teaching art, and collaborating with the visionary architect Antoni Gaudí in Barcelona. It was during his time in Barcelona, where Torres García also found an audience for his neoclassical paintings, that he developed the basis for an artistic philosophy that he would spend the rest of his life developing. Throughout his innovative explorations of the language of art, he never wavered from these two principles: that art, although inspired by nature, can provide a deeper view into reality by expressing more than the mere representation of what we perceive; and that art is always connected to the land and its cultures and traditions, going back throughout all of its history.

Torres García worked, for a time, creating a modern art form that was specific to the region of Catalonia—art that helped to define the Catalan identity by reaching back to the Mediterranean traditions of Greco-Roman classicism and connecting the idyllic rural scenes that were popular at the time with their rich regional history. After this period, his art began to evolve into a modernist abstract style as he began crafting inventive wooden toys. He restlessly moved his family about Europe, then to New York, then Italy, where he threw himself into the design and fabrication of his toys. But after problems mounted with that endeavor, he went back to his artistic roots in the Mediterranean, inspired once again to devote himself to painting. From there, he moved to Paris, becoming one of the founders of the Cercle et Carrét group of constructivist and other abstract artists, eventually moving on to Madrid to continue promoting constructivism. Finally heeding the call of the New World, he returned to Montevideo to begin an ambitious new project at the tender age of 60.

The constructive art movement was established upon one of the central principles that drove Torres García: that art can belong to a particular group of people. The movement had originated in Russia at the beginning of the twentieth century with the aim of inventing an art form that the working classes could call their own. It was a means by which to build an identity, a community, a consciousness. Russian constructivist art and industrial design strove to redefine the role of art in regular people’s lives, to produce art that, instead of being “fine,” was utilitarian. Abstract geometric forms distinguished this avant-garde style from traditional representative art, emphasizing the idea of a cultural revolution and reflecting the realities of the modern industrial world. Constructivism was eventually banned in Russia by Stalin, when he decided that abstractionism could not be understood by the proletariat, but experimentation with its progressive ideas about form and function and the spiritual nature of art was carried on by such adherents as the Russian artists who went to the Bauhaus in Weimar, Germany, De Stijl group in Holland, the St. Ives group in Cornwall, and the Cercle et Carré group in Paris, where Torres García taught that constructivism could revolutionize even as it connects the present with the past.

In his paintings, Torres García depicted the unity of the universe. In his writing, he called his philosophy “constructive universalism.” Onto a grid of shapes and colors—a conceptualization of a restructured universe, and by virtue of its abstraction, the joining of the material and the cognitive with the spiritual—he inserted recognizable symbols that allude to our humanity. Thus, on a two-dimensional plane, he was able to express the order of the cosmos—universal reason. The symbols are what draw the viewer in, representing culture, traditions, and nature with a power that societies going back to the beginnings of humanity have utilized as potent tools of communication. Torres García had increasingly found symbolism to be the link not only between each individual and our common humanity, but also between humanity and the cosmos.

Upon his arrival in Montevideo, Torres García was impressed with the vibrancy of the city, but soon found that artistic culture was sorely lacking. So he got busy. He joined in the struggle that artists throughout South America were waging against the popular sentimentalism for all things European, as they worked to develop their own South American artistic styles—new cultural languages that were distinct from the old European traditions—with Uruguay’s own Pedro Figari (whose visage and artwork adorns the Uruguayan 200-peso note) having been at the helm of the movement. With astounding energy, Torres García lectured and wrote and taught and gathered artists together and created paintings and designed murals, establishing the Escuela del Sur and literally turning the continent on its head with his now-iconic América Invertida, signifying that South America needed to stop looking at itself in the same old ways, as defined by others, and that the New World represented entirely new perspectives and new possibilities.

In turning South America upside down, Torres García was upholding the concept that art must come from the land and the culture and traditions that it has absorbed through its history. He recognized the wealth of cultural traditions that indigenous Americans had to offer, but not just for American societies, as he believed that these ancient cultures, through their rich symbolic languages, participate in a universal tradition that transcends the sphere of the relative and unites all into one cosmic truth. Torres García thus reinvented himself and his ideas, presenting a way for the people of the Americas to redefine their role in the world as a powerful new force of creative expression by both distinguishing themselves and, at the same time, uniting with all of humankind, and further, the universe. With this newly invigorated conception of constructive universalism, Torres García, like so many immigrants who brought cultural ideas from the Old World to transform them into truly unique New World traditions, had discovered America.

Square and Circle

Ayn Rand’s objectivist philosophy assigns to art the role of expressing abstract and metaphysical ideas, especially moral and ethical ideals, offering nothing explicit or fully conceptual, but rather, simply a sense of these ideas.

Rand admired romantic art for its allegorical reminders that it is only through personal volition that values are upheld. However, because objectivism’s emphasis on logic over emotion contradicts the sensual and emotional qualities that romantic art is steeped in, the term “romantic realism” was invented by artists who wanted to square off romanticism’s unruly, curvaceous emotionalism to fit into their faith in logic and reason. Conversely, trying to fit objectivist philosophy into any aesthetic at all is akin to trying to fit a square peg into a round hole.

To use another fitting metaphor, the way that objectivist philosophy was constructed was akin to trying to design a structure from the top down. The result is an unsound foundation. How fitting, then, that Rand uses the analogy of architecture to portray the supremacy of individualism over the stifling pressures of society in her novel The Fountainhead. The story can also be seen as a struggle to sever the ties that bind all of humanity together by denying the connective power of art as a cultural language, its ability to distinguish the individual while at the same time uniting individuals with the world, and its ability to shine its light into so many more facets of being than mere perception, strict reason, and linear logic can discover. By choosing architecture as her vehicle, Rand was faced with the contradiction between her romantic vision of the heroic individualist and her desire to find meaning in the act of creativity. Her protagonist, Howard Roark, is portrayed as a “prime mover” who wants to create pure, unmitigated, visionary art. But in order for him to be a true leader, he must engage with society and show qualities of leadership, not reject society entirely because it is flawed. His antagonists—the jealous, the manipulative, the power-hungry—embody those all-too-human characteristics that are the foundations of the ancient art of storytelling. Howard Roark’s tragic flaw is that he believes he is flawless, the “ideal man,” a god. He refuses to take personal responsibility for his inability to navigate the human landscape, to persevere, and to communicate his superior ideas in ways that others in his medium of choice—a highly collaborative art form—will respond to. This is, in fact, the burden of all artists, particularly the most imaginative, who must always find their way through the human landscape, with its pesky trends and popular opinions and cultural understandings, in order to continue.

Rand subsequently wrote about art as the transformation of abstract ideas into physical form—something to which others can respond emotionally—in recognition of the communicative nature of art. However, her reverse engineering exemplifies the unsoundness of her top-down design, as it falls short of explaining why art’s communicative nature would be important to individuals, if not as a connective force. It leaves Howard Roark to his lonely world, where individuals exist disembodied from their cultural ecosystems, independent of the need to connect with something larger than themselves, detached from the interchange of ideas across time and space and cultural worlds that is the true engine of innovation.

Moving from metaphoric physical structures to metaphysical structural forms, objectivism begins not as its name suggests, with the notion that reality exists independently of our consciousness of it, but rather, with the characterization of individualism as unfailingly strong and virtuous, while cooperation and compassion can only be weak and decadent. Working backward from the idea that individual happiness as a moral virtue is the highest purpose of human life, it jumps to the conclusion that, if individuals must be left to navigate the world independently of what all other individuals think, if individual experience is really all that is important, then the human mind must be able to observe a single absolute reality—because otherwise, there would be no contiguity between each individual’s independent perceptions of the universe. It is a stingy, fragmentary, solitary philosophy that speaks from the mind’s desire to divide and conquer the universe.

In turn, by examining the metaphysical structure of constructive universalism, the exquisite elegance of the aesthetic as the atom of our humanity reveals itself: We communicate; therefore, we are human. It begins with the artist’s self-knowledge that creativity is a function of humanity’s intrinsic need to reach out to other human beings, with the understanding that the universe is full of possibility and is infinitely imaginable—the white canvas transformed into realities that we constantly create and re-create. From this foundation follows what Torres García understood as the connection of art to the land and its culture and traditions. Humans develop languages with which we share ideas, experiences, information, values—with which we restructure the universe so we can comprehend it, engage with it, not only survive it, but shape it. The languages of words are certain ways of organizing the universe, as are the languages of music, theater, dance, ritual, symbolism, and plastic arts, each achieving different levels of understanding—the plastic arts, by intuiting meaning in such elements as shape, color, play of light, spatial structure, perspective, and dimension. Various languages shared among groups of people over time become cultural traditions that define who we are and where we have come from, confirming our individual identities though our communication and connection with others. It is a magnanimous, contiguous, connective philosophy that speaks from the center of our humanity.

Connections

Joaquín Torres García’s artistic innovations, as different as they were from anything that came before them, emerged from cultural traditions of the past and conditions of the present, and from the artist’s personal experiences, sentiments, and opinions. Likewise, Ayn Rand’s ideas did not arise in a vacuum. They were, in no small part, a direct reaction to her personal past, having been the teenaged daughter of bourgeois Jewish parents in St. Petersburg when the Russian Revolution broke out in 1917 and fleeing with her family to Crimea when the Bolsheviks came to power. Her ideas were a product of her time, her locations, her experiences. When she came to the United States in 1925 at the age of 20, she, too, was greatly impressed with the New World vitality, quickly immersing herself in its cultural currents.

The romantic image of the self-reliant pioneering spirit, the rugged individual, the self-made individual, has been a cultural staple throughout the history of the United States of America. It is the American Dream. And the narrative of freedom versus tyranny that defines the battle of political capitalism against socialism has also become a part of the fabric of society in the United States, a thread that Rand was quite keen to pull at. But in her passion to expound upon this cultural narrative, which she came to with the authority of her personal experience as an opponent of communism in Russia, she inherited the same tragic flaw that is inherent to this narrative, that is, its refusal to be self-critical, which prevents it from finding real answers to real problems. This amounts to an illusory disassociation from the fabric of space, time, and thought that is ultimately as unsustainable as wanton consumerism and the profligate burning of fossil fuels. By separating, simplifying, rationalizing, and romanticizing, objectivism severs itself from the possibility of reaching out to people around the world who are not culturally primed to believe that selfishness is a virtue, or that we are not all interconnected in infinite ways on this planet that those of us who speak English call “Earth.” Instead of innovating, objectivism was shaped into the mold that the United States had formed for itself—big and bold and self-assured, culturally uninterested in the fate of its neighbors (although not afraid to quietly engage economic exploitation or political meddling), tragically oblivious to the fact that America actually stretches from the Arctic Circle to Tierra del Fuego. For an idea or a nation to truly be a “prime mover,” it must understand its connections, in as many dimensions as imaginable, to the universe all around.

Back to Uruguay

Eduado Galeano is another Uruguayan and another connective thinker. He is a journalist who also writes about the interconnectedness of the world by following common threads of history that are woven into the fabric of the present. He is a critic and a cynic who frankly addresses realities that can be difficult to face. He does not always paint pretty pictures, nor does he communicate through abstraction, nor invent fiction. In his literature, he creates a vast mosaic of diverse stories—occasionally mythical, often having been subverted, many about independent women, always with a keen sense of irony, reaching back into prehistoric times, across many different cultures of the world—that all mirror who we are today. In a passage from his book Mirrors: An Almost Universal Story, Galeano poses some interesting questions about the most basic nature of humanity:

Ser boca o ser bocado, cazador o cazado. Ésa era la cuestión.

Merecíamos desprecio, o a lo sumo lástima. En la intemperie enemiga, nadie nos respectaba y nadie nos temía. La noche y la selva nos deban terror. Éramos los bichos más vulnerables de la zoología terrestre, cachorros inútiles, adultos pocacosa, sin garras, ni grandes colmillos, ni patas veloces, ni olfato largo.

Nuestra historia primera se nos pierde en la neblina. Según parece, estábamos dedicados no más que a partir piedras y a repartir garrotazos.

Pero uno bien puede preguntarse: ¿No habremos sido capaces de sobrevivir, cuando sobrevivir era imposible, porque supimos defendernos juntos y compartir la comida? Esta humanidad de ahora, esta civilización del sálvese quien queda y cada cual a lo suyo, ¿Habría durado algo más que un ratito en el mundo?

(My translation)

To eat or be eaten, hunt or be hunted. That was the question.

We deserved disdain, or at most, pity. Exposed to the elements, no one respected us and no one feared us. The nighttime and the jungle terrorized us. We were the most vulnerable creatures of the terrestrial zoology, useless as pups, as adults, little more, without claws, nor large fangs, nor fast feet, nor a long nose.

Our first story we lost in the mists of time. It would seem that we were dedicated to no more than throwing stones and exchanging blows.

But one may well ask, Had we not been able to survive, when survival was impossible, because we knew to defend ourselves together and to share food? This humanity of today, this culture of save oneself who can and each one for themselves—could it have lasted any more than a short time in the world?

The expansive power of the connective idea that the small South American nation of Uruguay illuminates, like a lighthouse on a rocky cape, never ceases to amaze me. After my first experience here, then learning more and more about Uruguay’s artistic and intellectual culture, I continue to find inspiration in the idea that, at the heart of our humanity, lies the drive to connect. While the mind wants to divide the universe up into definable segments, assigning a word to each diminishingly tiny particle, the spirit reunites, seeking meaning, continuity, and the ever-expanding vision that can see unity in infinity.

The expansive power of the connective idea that the small South American nation of Uruguay illuminates, like a lighthouse on a rocky cape, never ceases to amaze me. After my first experience here, then learning more and more about Uruguay’s artistic and intellectual culture, I continue to find inspiration in the idea that, at the heart of our humanity, lies the drive to connect. While the mind wants to divide the universe up into definable segments, assigning a word to each diminishingly tiny particle, the spirit reunites, seeking meaning, continuity, and the ever-expanding vision that can see unity in infinity.

Language, culture, the incessant flow of water, as of time, the energies held close by the land through which the waters of life flow, through which life itself flows, along with people, and ideas, and memories, and love… These are all connective forces, and to deny their power is to sever the veins that animate our infinitely interconnected biosphere for the sake of the human mind’s fleeting illusion that we can know, through reason and logic alone, what truth is—or who we really are.

.jpg)

No comments:

Post a Comment